Metastatic breast cancer cells that spread to the lung do not tend to be cells undergoing the epithelial-mesenchymal (EMT) transition, says a Weill Cornell Medical School team in a newNature study.

The finding contradicts the commonly held belief that EMT cells–which many, if not most, cancer researchers believe are cancer stem cells–are the main cells that metastasize.

“Blocking EMT seems to not impair metastasis, at least in animal models, as evidenced by both our study and a back-to-back [pancreatic cancer] paper in Nature,” senior author Ding Cheng Gao, Ph.D., a Weill Cornell developmental biologist in cardiothoracic surgery, told Drug Discovery & Development. “Combining anti-EMT and chemo therapies should benefit most patients.”

“These new findings are significant, challenging the somewhat dogmatic view EMT is required for epithelial tumor metastasis,” University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute Associate Professor Alma Welm told Drug Discovery & Development. “While an EMT phenotype in vitro has long been associated with tumor aggressiveness and metastasis in vivo, there has been scarce in vivo data. In recent years, data have shown cells undergoing EMT may need to revert to an epithelial state to colonize and grow in the metastatic site. A reversible EMT-MET may explain why most metastases predominantly display epithelial features, but the new data support a model in which epithelial cancer cells metastasize without undergoing EMT up front, and show a role for EMT in drug resistance consistent with work showing EMT conveys stem cell-like features on cancer cells.”

She concluded: “It appears EMT is a program facilitating a plasticity that favors adaptation to various types of stress, an obvious advantageous feature for cancer cells.” Welm was uninvolved in the study.

The EMT theory

For a long time, many researchers believed the epithelial cells in breast cancer must revert to a kind of stem-cell state, going through the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, in order to break away and metastasize.

But the new study finds that, while breast cancers do possess these stem-like cells–which again, the Weill Cornell group refers to as EMT cells– other more proliferative, and more differentiated, breast cancer cells may be the mobile cells.

Later, the study finds, post-chemo the opposite occurs. That is, at that later post-chemo juncture, it is indeed the stem-like EMT cells that prompt metastasis, apparently having been chemo-resistant.

The work

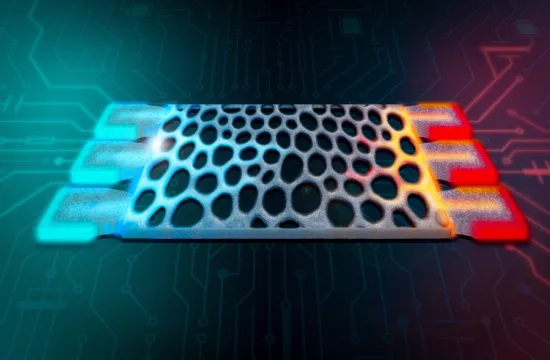

To come to their conclusions, the Weill Cornell group, with teams from Columbia University, Houston Methodist Research Institute, and Soonchunhyang University in South Korea, created a new approach they called “EMT cell lineage tracing,” which follows single breast cancer cells in mouse models of metastatic breast cancer.

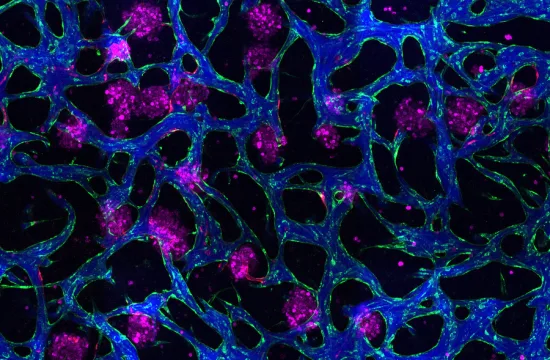

The breast cancer cells were engineered to emit a red fluorescence, then emit a green fluorescence when EMT occurred. At first they saw largely red cells. But the cells that broke off and traveled to the lung were also red, not green as expected.

For confirmation, the teams used an EMT inhibitor. This did not affect lung metastasis. The team then gave their mice chemo. The chemo wiped out the glowing red cells — including those in the lungs — but not the green EMT (stem cell like) tumor cells.

The teams at that point at last saw green metastatic lesions in the lung, lesions hailing from the stem-cell like EMT cancer cells, suggesting that these cells had been chemo-resistant from the start.

Finally, the teams gave the mice a combination of chemo and their experimental EMT blocker. No metastasis occurred.

Gao’s team is now testing different therapy combinations in their EMT lineage tracing system.

Earlier Nature study

An earlier Nature study found that EMT stem-cell like cells, at the edges of primary tumors pre-metastasis, were unlike more differentiated primary tumor cells. That paper also revealed that same EMT stem-cell signature in early circulating tumor cells (CTCs).

Later, that paper found metastatic cells that successfully moved to other tissues were generally not stem-cell like. They were more differentiated, like the original primary tumor cells.

[pullquote]In an accompanying News & Views, Haber and MGH biologist Shyalama Maheswaran, Ph.D., warned more genetic EMT switches should be studied.[/pullquote]

“I did not see a big contradiction between that earlier stem/EMT signature paper and our study,” Gao told Drug Discovery & Development. “Instead, the two studies complement each other somehow” in that the successful metastases, surviving the move to other organs early on, did not seem to express many stem cell markers in either study.

Furthermore, Gao said: “I was not surprised to see higher stem/EMT marker expression in CTCs or metastatic cells from lower burden tissue in the other paper. It is true still that EMT tumor cells have some advantages in dissemination.”

University of California Irvine assistant professor of physiology and biophysics Devon Lawson, Ph. D., was lead author of that earlier Nature paper. She told Drug Discovery & Development she agreed that “it’s likely that [Gao’s] findings do not conflict with ours. Although I noted there was an increase in several EMT genes in ‘early’ low burden met cells in our study’s PDX models, I did not do any functional experiments to address whether this was functionally significant. Therefore, although they may be increased in expression, it may not be necessary for them to disseminate.”

She also noted there are many different kinds of EMT genes.

“I think they’re looking at different things,” Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center Director Daniel Haber, M.D., Ph.D., told Drug Discovery & Development. Haber was uninvolved with the study. “The fact that EMT may not be required to trigger metastasis doesn’t exclude other pathways being relevant or important. The fact that proliferative signatures get upregulated, as `stem-like’ quiescent metastatic cells start to grow into metastatic tumors, also makes sense. I’d summarize that they’re looking at different parts of the same process (i.e., how cancer cells disseminate, and then start to grow), and this isn’t fitting into a single strict pathway.”

Welm agreed. “These new data don’t contradict the recent data published by Lawson et al, which showed that metastatic cells had properties of stem cells, EMT, pro-survival, and dormancy-associated genes–but did not directly implicate EMT in the metastatic process,” she told Drug Discovery & Development. “Instead, they showed that the conversion from a ‘dormant’ to an active state required Myc-CDK activation, which could happen irrespective of the EMT status of the cell.”

Ultimately, Gao thinks it doesn’t matter what one calls any of the cells. “The EMT tumor cells are definitely expressing more stem cell markers, and behave like stem cells, including the fact that they are slower proliferating,” he told Drug Discovery & Development. But “EMT is reversible…It will be hard—or not critical—to determine which are the stem cells. What matters is the ability of tumor cells to make the transition, to transform their phenotype. In the end, we need to target this transiting ability to kill tumor cells more efficiently.”

He concluded: “Targeting metastasis is the critical next step.”

Re-evaluation of EMT’s role

In an accompanying News & Views, Haber and MGH biologist Shyalama Maheswaran, Ph.D., warned more genetic EMT switches should be studied.

Still, they wrote: “Nonetheless, the conclusions reached by the two [back-to-back pancreatic and breast cancer] studies warrant a re-evaluation of the role of EMT in cancer progression. Alternative ways in which epithelial cells could enter the bloodstream without acquiring mesenchymal properties, such as collective epithelial-cell migration or tumor fragmentation, are worth investigating.”

They also agreed a late-in-the-game switch back to the EMT stem-cell state may indeed prompt chemo-resistance. “The postulated role of EMT in mediating cancer-cell survival is reinforced by the two latest studies,” they wrote. “Indeed, EMT has been linked to drug susceptibility of cancer cells, as well as to their entrance into a non-proliferative state in which they have stem-cell-like properties. Understanding the many cellular pathways that together determine these cell fates, and how these pathways are modulated, is likely to provide fertile ground for drug discovery.”