Observations of the formation of light-nuclei from high-energy collisions may help in the hunt for dark matter

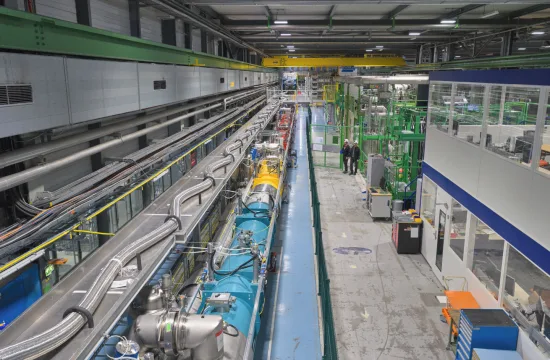

Particle collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) can reach temperatures over one hundred thousand times hotter than at the centre of the Sun.

Yet, somehow, light atomic nuclei and their antimatter counterparts emerge from this scorching environment unscathed, even though the bonds holding the nuclei together would normally be expected to break at a much lower temperature. Physicists have puzzled for decades over how this is possible, but now the ALICE collaboration has provided experimental evidence of how it happens, with its results published today in Nature.

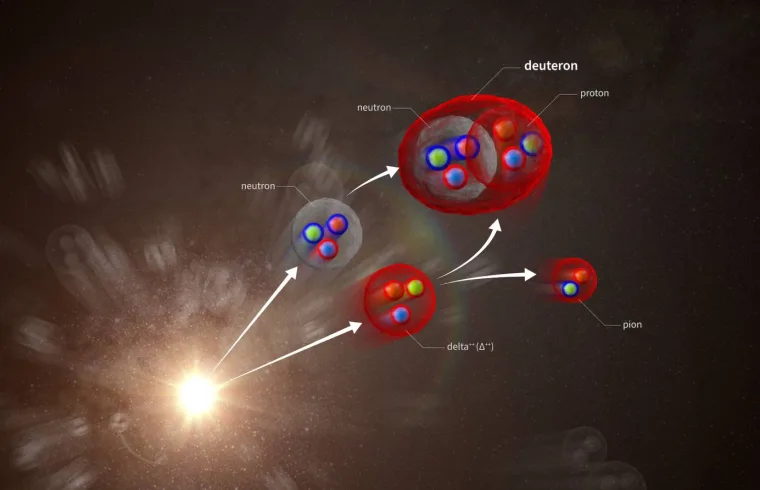

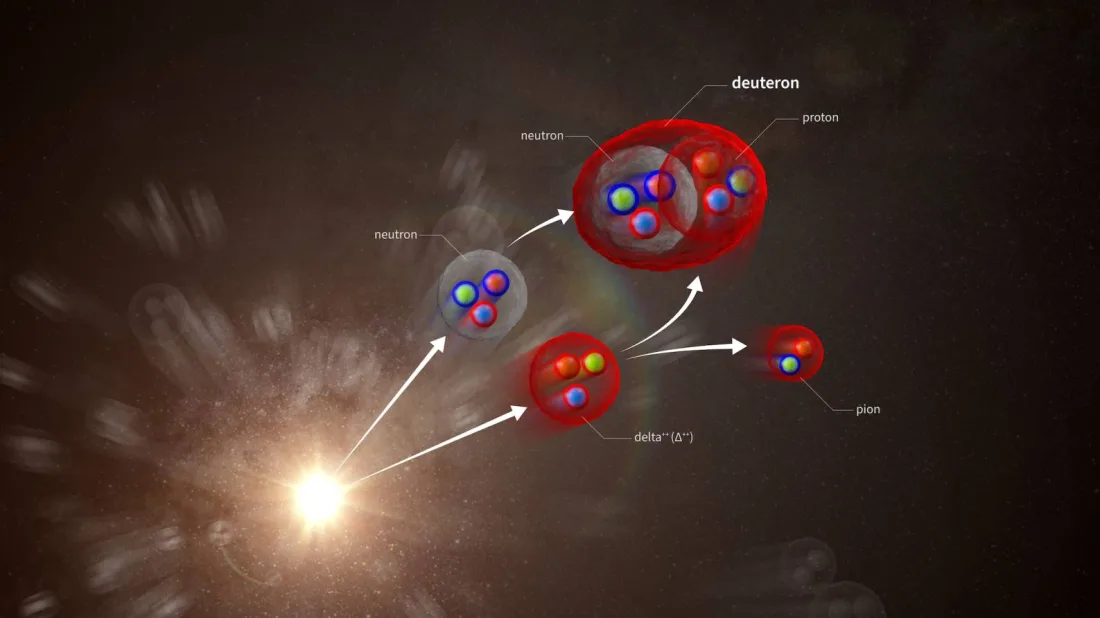

Researchers at ALICE studied deuterons (a proton and a neutron bound together) and antideuterons (an antiproton and an antineutron) that were produced in high-energy collisions of protons at the LHC. They found evidence that, rather than emerging directly from the collisions, nearly 90% of the deuterons and antideuterons were created by the nuclear fusion of particles emerging from the collision, with one of their constituent particles coming from the decay of a short-lived particle.

“These results represent a milestone for the field,” said Marco van Leeuwen, spokesperson for the ALICE experiment. “They fill a major gap in our understanding of how nuclei are formed from quarks and gluons and provide essential input for the next generation of theoretical models.”

These findings not only explain a long-standing puzzle in nuclear physics but could have far-reaching implications for astrophysics and cosmology. Light nuclei and antinuclei are also produced in interactions between cosmic rays and the interstellar medium, and theymay be created in processes involving the dark matter that pervades the Universe. By building reliable models for the production of light nuclei and antinuclei, physicists can better interpret cosmic-ray data and look for possible dark-matter signals.

The ALICE observation provides a solid experimental foundation for modelling light-nuclei formation in space. It shows that most of the light nuclei observed are not created in a single thermal burst, but rather through a sequence of decays and fusions that occur as the system cools.

The ALICE collaboration came to these conclusions by analysing the deuterons produced from high-energy proton collisions recorded during the second run of the LHC. The researchers measured the momenta of deuterons and pions, which are another type of particle formed of a quark–antiquark pair. They found a correlation between the pion and deuteron momenta, indicating that the pion and either the proton or the neutron of the deuteron actually came from the decay of a short-lived particle.

This short-lived particle, known as the delta resonance, decays in about one trillionth of a trillionth of a second into a pion and a nucleon, i.e. either a proton or a neutron. The nucleon can then fuse with other nearby nucleons to produce light nuclei such as a deuteron. This nuclear fusion happens at a small distance from the main collision point, in a cooler environment, which gives the freshly created nuclei a much better chance of survival. These results were observed for both particles and antiparticles, revealing that the same mechanism governs the formation of deuterons and antideuterons.

“The discovery illustrates the unique capabilities of the ALICE experiment to study the strong nuclear force under extreme conditions,” said Alexander Philipp Kalweit, ALICE physics coordinator.