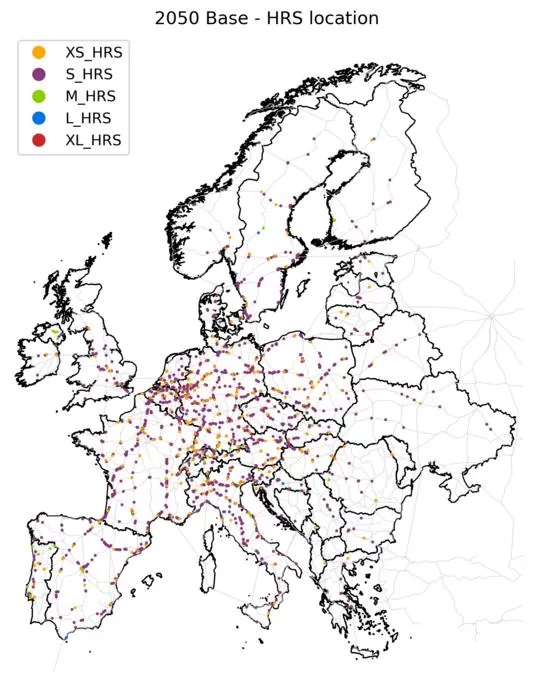

As hydrogen infrastructure is rolled out in the EU, refueling stations must be distributed according to the same principle in all countries.

But now a study from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden points to shortcomings in EU regulations. Using an advanced model, the researchers show that the distribution of refueling stations may be incorrectly dimensioned and lead to losses of tens of millions of euros a year in some countries.

By 2030, EU countries must have built hydrogen refueling stations at least every 200 kilometers on major roads and one in every urban node. The aim is to facilitate the introduction of hydrogen-powered transport. This is governed by the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR), which entered into force in 2023.

However, a study from Chalmers, based on data from 600,000 freight routes across Europe, shows that in many cases the requirements do not reflect actual demand. By modeling how hydrogen-powered long-haul trucks might operate in 2050, researchers show not only where demand for hydrogen infrastructure will be highest but also how current EU rules risk leading to large losses in some countries.

“EU law is based on distance, but traffic volumes differ in other ways between countries. According to our model, capacity in France needs to be seven times higher in 2050 than what the EU requires by 2030. Consequently, the rollout under AFIR works as a first step on the way but will need to be supplemented,” says Joel Löfving, doctoral student at the Department of Mechanics and Maritime Sciences at Chalmers.

However, countries such as Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece do not have the same traffic flows, and they are being forced to build infrastructure that is unlikely to be used to the same extent. This may amount to tens of millions of euros a year in investment and operating costs for unused capacity.

Accurate simulation reflects demand

In addition to taking into account traffic volumes and distances, the Chalmers study includes topographical data from the European Space Agency. One important insight is that geographical terrain plays a greater role in energy demand than was previously assumed.

“Many models use an average energy demand per kilometer for trucks. However, the demand profile changes markedly when parameters such as gradient and speed are included. This gives you a more accurate basis for where the infrastructure may be needed,” says Joel Löfving.

The study focused on long-haul traffic, i.e., distances of more than 360 kilometers, as shorter distances are likely to be covered by battery-powered goods vehicles in the future.

“We considered the direction of technology development for trucks. Much of the current research shows that batteries will be able to cover the shorter distances, while alternatives such as hydrogen may be needed as a supplement for long distances,” says Joel Löfving.

Political interest in demand-based rollout

The researchers’ model looks further than the 2030 requirements and analyzes how investments in hydrogen infrastructure can be sustainable in the long term. The study has already been used to inform political discussions in both Sweden and the EU on how to plan the rollout of hydrogen infrastructure.

“At EU level, we have been able to provide feedback for the evaluation of AFIR that will take place in 2026, and I hope to influence the development of the law in a way that takes into account each country’s specific circumstances. For Sweden, AFIR is a good start, but investing in expensive new technology is always risky. Because the study has a longer time frame, we have been able to contribute to the discussion on how to build an economically sustainable refueling station network that will eventually make it easier to create a market for heavy hydrogen vehicles,” says Löfving.