MADISON — David O’Connor believes poop can tell you a lot about yourself and those around you — and there’s science to back him up.

While analyzing data from wastewater samples collected by the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene earlier this year, O’Connor and his colleagues detected a highly mutated version of the virus that causes COVID-19 called a cryptic lineage. With some careful scientific sleuthing, they were able to track the lineage to a single source.

What’s curious about cryptic lineages is that, through some unknown process, they develop the same spike gene mutations found in variants of concern, like omicron, despite not being descended from these or related strains. Scientists are interested in studying these lineages, which might be the origin of the next major COVID variant and a widespread wave of infection.

“How could one person’s virus shed into wastewater have many of the same changes that took the [omicron variant] over two years to ‘figure out’ as it spread through the world? That’s the huge question we are trying to figure out,” says O’Connor, a professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

This is why he and his team were so keen on tracking the lineage they detected back to its source. Their findings are the subject of a study published ahead of peer review on Nov. 1 in medRxiv and the focus of a recent story published in Nature this September.

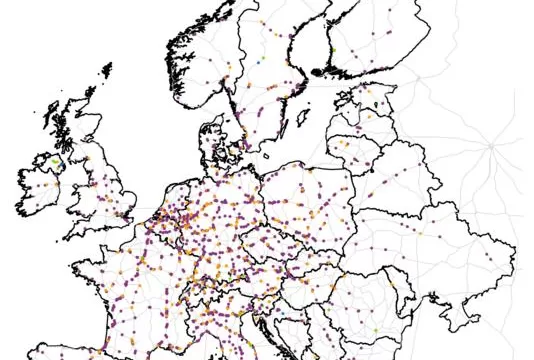

“It’s like CSI Sewer,” O’Connor explains. “We had a map of where the manhole locations were (where the wastewater samples originated), so we would strategically try to choose which ones would allow us to narrow the source.”

By eliminating the samples that were negative for the cryptic lineage and tracing the positive manholes around the map, the team could determine the specific office building from which the lineage was being expelled. The team’s goal is to test the office workers in the building to see if they can pinpoint the individual shedding the unique virus.

If they can find this person, they may be able to better understand how infectious the cryptic lineage could be and whether it can survive outside the gut environment.

But doing so requires office workers to volunteer themselves for testing. Some of the workers in the building agreed to nasal swabbing, but the researchers have yet to see the same cryptic lineage in those samples.

That raises a few questions: Is the individual with the cryptic lineage not one of the workers who volunteered for a nasal swab? Is the virus detectable in waste but not in the nasal passageway? Or, is the individual even shedding the virus anymore?

The next step in tracking down the individual is to collect fecal samples from the office workers.

Finding this cryptic lineage in Wisconsin also made O’Connor wonder how many other people around the country and the world had similar mutations, with unknown levels of infectiousness. He says he can imagine a world where the infrastructure for regular wastewater monitoring exists all the time, giving scientists access to community infection rates without reliance on individual testing.

After all, COVID fatigue is real. Many fewer people are seeking out PCR testing, maybe to avoid the brain-scraping feeling of nasal swabs, because they’re finding less testing availability in their communities or, like many people, because they’re shifting into a post-pandemic mindset.

Since it isn’t realistic to expect everyone in a community to test all the time, passive community testing like wastewater sampling provides a sort of happy medium. So, too, might another passive approach: vacuuming up what’s floating in the air.

Across the hall from David O’Connor, another researcher’s lab is studying respiratory viruses that might be found in the air in places like schools and nursing homes. Meet Shelby O’Connor, a professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at UW–Madison, who also happens to be married to David.

Through a partnership with Thermo Fisher that began last year, Shelby’s lab has been collaborating with David’s to monitor the presence of COVID-19 using AerosolSense instruments that suck up air and trap the stuff floating in it on foam cartridges.

So far, they’ve placed devices in public schools, nursing homes, and David’s lecture class at UW–Madison, where they collect air for a day or two, gobbling up viruses and whatever else is floating around.

Back in the lab, the O’Connors and their team use a solvent to squeeze everything the sponge captured into a tube.

Since the air sampling devices collect more than just viruses, the researchers then conduct tests to see if potential viruses of concern are present and work to identify the ones that are.

They do this through a process called sequencing, where they look at the basic building blocks of viral genetic material that may be present in their sample, called nucleotides, and the order in which they’re strung together. That ordered string can then be used to identify what viruses the team is seeing in a sample.

Sequencing can be used to look specifically for COVID-19 but also to zoom out and identify other respiratory viruses, like influenza or other unknown viruses, that may be present in the air. Being able to look both specifically and broadly gives the researchers the potential to monitor the air in these locations for viruses that could lead to future outbreaks.

“What’s interesting is we have seen different viruses showing up in different populations,” Shelby says. “For example, on the university campus, we saw influenza in late 2021, but in the surrounding K-12 schools where we were running these samplers, we did not see influenza.”

Strategically placing these devices may help high-risk communities prepare for potential disease outbreaks, allowing them to adopt mitigation strategies to help keep patients in nursing homes safe and schools open.

Their further studies could also present an opportunity for tracking and understanding local infection rate data. For instance, researchers could create a dashboard for specific buildings and high-traffic areas, such as airports, so people visiting or passing through can be better informed on their risk of exposure to various viruses.

A central theme of both David and Shelby’s research revolves around conducting science that makes data actionable and impactful for non-scientists. Despite COVID fatigue, Shelby and David’s teams have continued collaborating with other scientists and community partners.

“I think it’s really great when we get to work with people who are also as excited to help each other as we are. It’s been really nice to see how many people can be community-focused, through this process,” Shelby says.

In the O’Connors’ ideal world, air sampling devices would be in every airport and sewer system, constantly collecting data and helping the public stay more informed about disease risks.

But while these technologies are moving further from science fiction and closer to reality every day, the O’Connors stress that it’s important for people to continue using the effective mitigation tools we already have to prevent the spread of respiratory diseases like COVID-19 and flu. Masks, regular handwashing, staying home if you feel sick, and staying up-to-date on available vaccines are all steps people can take to protect themselves and each other.

“You have to still recognize your risk in particular situations,” Shelby says. “Even if scientists are doing their darndest to predict the best they can, it’s still biology. There are things we can’t control, and so you have to still take care of yourself.”