The deadly, record-breaking heat wave that hit the Pacific Northwest in June 2021 continues to be the subject of intense interest among scientists, policymakers, and the public.

A new study from some of the region’s top climate scientists synthesized more than 70 publications addressing the causes and consequences of the extreme heat wave and the potential for similar high-heat events to happen in the future.

“It’s still the event of interest for anyone who studies heat waves or the atmospheric patterns that cause them,” says Paul Loikith, associate professor of geography in Portland State’s School of Earth, Environment, and Society and a co-author of the study.

Researchers in the Pacific Northwest and around the world agreed that the heat wave was caused by a rare and complex combination of meteorological factors.

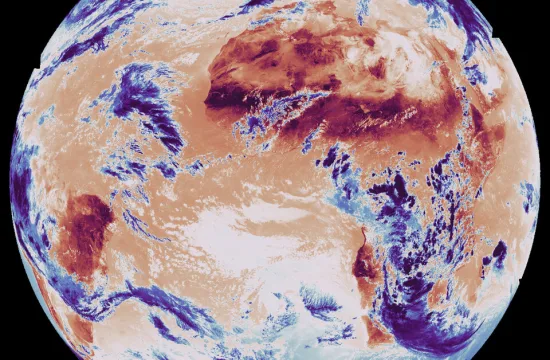

The primary driver was a persistent, extraordinarily strong ridge of high pressure—often called a “heat dome”—that trapped hot air over the region. Other contributing factors included moisture from the tropical Pacific Ocean, high solar radiation, low pressure offshore, sinking air over land, and unusually dry soils.

Loikith says there’s no consensus that ridges of high pressure similar to the one that drove this event will become significantly more common, but as the climate continues to warm, the temperatures experienced during the 2021 heat wave, such as 108, 112, and 116 degrees Fahrenheit over three consecutive days in Portland, will become more frequent.

“Essentially, you don’t need a high-pressure ridge of that magnitude to create a heat wave of that magnitude,” Loikith said.

“As you get into a warmer climate, you could have a weaker feature in the atmosphere, leading to the same temperatures because the overall background climate is getting hotter.”

He says the likelihood of reaching 116 degrees Fahrenheit in Portland again is increasing over time, but the probability is still fairly low.

“By the end of the 21st century, a heat wave of this magnitude potentially could be experienced once a decade or maybe even more frequently under a higher emissions scenario,” Loikith said.

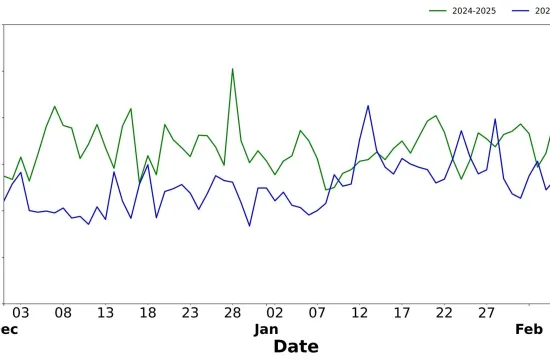

Whether the region experiences another heat wave of equal magnitude this summer or next summer can’t be predicted more than one or two weeks in advance.

“Portland summers have warmed by a lot over the last 80 years—four, even five degrees Fahrenheit—but the 2021 event was almost 40 degrees Fahrenheit above average,” Loikith said.

“Putting that into context, we’re seeing this steady, gradual warming. We will still have some cooler summers and warmer summers. The cooler summers are warmer than cooler summers were in the past, and the warmer summers are warmer than the warm summers in the past.”

The researchers say that there is still much to learn about the atmospheric drivers and long-term impacts of these extreme weather events.

The 2021 heat wave had compound effects on human health and ecosystems. Mortality, heat-induced illness, and the number of visits to emergency departments were anomalously high, with the greatest impact among older adults, individuals living alone, those with lower incomes, and those without working air conditioning. Browning or scorching of tree leaves and needles following the heat wave was extensive, although the extent of long-term tree mortality is not yet clear.

Following the heat wave, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia established new initiatives to reduce the risk of heat-related illness, including workplace regulations and new programs to provide cooling devices to populations at greatest risk, but the researchers anticipate it will be several years before the effectiveness of these new interventions is known.

“This is an example of why we need to study these things so that we can better understand them and better predict what their likelihood is going to be in the future,” Loikith said.

“The studies that we reviewed in this paper help us understand things as basic as atmospheric theory, like things that we still don’t fully understand about the atmosphere, all the way to impacts on ecosystems and people and everything in between. We are still learning, and that’s making us more prepared.”

The study was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Loikith was joined in the study by Oregon State University’s Erica Fleishman, director of the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute and lead author; David Rupp, an associate professor and researcher with OCCRI; Larry O’Neill, Oregon’s state climatologist; and Karen Bumbaco, Washington’s deputy state climatologist.