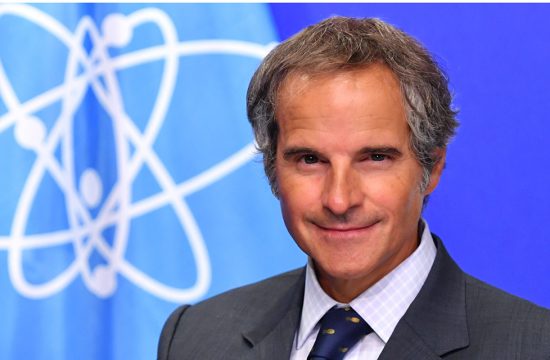

Prof. Dr. Urs Gasser heads the Chair of Public Policy, Governance, and Innovative Technology at the Technical University of Munich (TUM). He is Dean of the TUM School of Social Sciences and Technology and Rector of the Munich School of Politics and Public Policy (HfP) at TUM. Previously, he served as Executive Director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University and as a professor at Harvard Law School.

How can quantum technologies be developed responsibly? In the journal Science, researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), the University of Cambridge, Harvard University, and Stanford University argue that international standards should be established before laws are enacted.

Prof. Urs Gasser explains why the authors propose a quality management system for quantum technologies, how standards create trust, and where even competing countries such as China and the US can cooperate.

Quantum technologies could have an even more disruptive impact than artificial intelligence. This is why there are growing calls to steer technological development in a socially responsible direction at an early stage through legislation, unlike with AI. Why do you see things differently?

We are not fundamentally opposed to legal regulation. At a later stage, when the applications of quantum technologies are more clearly foreseeable, legislators should draw red lines, particularly for high-risk applications. However, in the current early development phase, we believe that a different approach is more promising for achieving goals such as security, interoperability, transparency, and accountability: the creation of international technology standards on which legislation can be based. In other words: standards first.

This sounds like we want to get to grips with the most complex technology in history using DIN standards.

Precisely because the technology is so complex, technical standards must come first. The issue becomes clear in the case of AI regulation in Europe, where the reverse approach was taken: we now have an EU AI Act, but standards will need to be developed feverishly in the coming years to understand what the regulation means and what compliance looks like in practice. This can create significant legal uncertainty and strain the innovation climate at a critical moment.

Are there any examples of successful standardization of complex technologies?

Numerous technologies have been guided by standards on which regulation could be based. For example, the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) has created essential standards for information security, which are crucial for companies in all industries—and thus also for their customers—in the protection of sensitive data in the digital age. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) has established safety requirements for medical electrical equipment to ensure the protection of patients and users. And the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has created the technical basis for Wi-Fi with its standards for wireless networks, enabling devices from different manufacturers to communicate seamlessly with each other. In a similar way, we can now also define protocols, interfaces, and numerous technical specifications for quantum technologies.

What standardization work is already underway, and what should be done now?

A wide range of standardization processes is already underway at the international and national levels. For instance, ISO and IEC established Joint Technical Committee 3 (JTC 3) in early 2024 to develop fundamental standards for quantum computing, quantum communication, and related areas. The IEEE, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) are also working on standards for post-quantum cryptography, interoperability, security, and performance benchmarks.

Building on this, our proposal recommends the introduction of a certifiable quality management system (QMS) for quantum technologies. This would not only take technical aspects such as stability and security into account but also systematically integrate legal, ethical, and thus socially relevant aspects into development and operation. It won’t be the individual product that is certified, but the company’s management system—similar to the current practice in medical technology. Such certificates could be issued by independent, accredited bodies such as TÜV once a standard has been defined. This would create a trustworthy framework that ensures quality, transparency, and accountability.

Given the technological and economic competition, is it realistic to expect an international agreement on such a system?

Standards facilitate international cooperation even where political cooperation is currently lacking—for instance, between China, the United States, and Europe. In committees such as ISO, IEC, and IEEE, experts develop globally recognized rules that create trust in new technologies and give companies security for their investments. In addition, these soft laws are more flexible than traditional laws, as they can be quickly adapted to technical developments, thus facilitating innovation without losing sight of the risks.

Isn’t that a very technocratic process lacking democratic legitimacy?

Standard setting is certainly not a classic democratic process, such as parliamentary legislation. Nevertheless, it is not a closed expert system. International standardization organizations often bring together various stakeholders, including companies, civil society groups, research institutes, and public authorities. In national committees that help shape international work, different interest groups are often even more closely involved. In addition, many standards today are developed not only to address technical issues but also increasingly to take ethical, social, and legal aspects into account – for instance, in areas such as data protection, security, or inclusion. Social values, risks, and rights are an integral part of standards for quality management systems in particular.

At the same time, there is justified criticism. Some standardization processes are dominated by economically powerful actors, and social perspectives are not equally represented. These shortcomings are well known and are increasingly being addressed—for example, in current debates on the development of AI standards in Europe, where conscious efforts are being made to give greater consideration to civil society voices and fundamental rights issues.

It is important to note that standards do not replace political regulation. Rather, they can precede it and establish a compatible foundation. The actual regulation remains the task of democratic institutions, which establish legally binding frameworks on this basis, adapted to national contexts and societal debates.