Some traumatic experiences, like childhood abuse, are so painful that the brain tucks them away in a special chemical pathway in the brain, according to a new study.

Some traumatic experiences, like childhood abuse, are so painful that the brain tucks them away in a special chemical pathway in the brain, according to a new study.

Those same memories might be retrievable – and treatable – by recreating that same pathway with drugs, according to the research, published today in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

“The brain functions in different states, much like a radio operates at AM and FM frequency bands,” said Jelena Radulovic, principal investigator and Dunbar Professor in Bipolar Disease at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “It’s as if the brain is normally turned to FM stations to access memories, but needs to be tuned to AM stations to access subconscious memories.”

Two amino acids that function as the “yin-and-yang” of the brain, glutamate and GABA, normally control the “tides” of emotions, according to Radulovic. But the independent agent known as the extra-synaptic GABA receptor can itself change the brain’s state, from fatigued to sedate, inebriated or even psychotic, she added.

The extra-synaptic GABA receptors also encode the memories of extreme fear and stress events, they found.

“If a traumatic event occurs when these extra-synaptic GABA receptors are activated, the memory of this event cannot be accessed unless these receptors are activated once again, essentially tuning the brain into the AM stations,” Radulovic said.

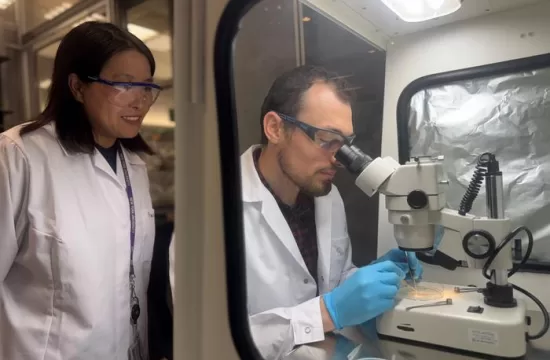

The mouse experiments to test the chemical pathway involved infusing the rodents’ hippocampuses with gaboxadol, a drug that stimulates the receptors.

When the mice were put in a box and given a shock, they expressed fear. When they were put in the box the following day, drug-free, they moved around and did not remember the shock. But when they were again given the drug and put in the box, they froze in place.

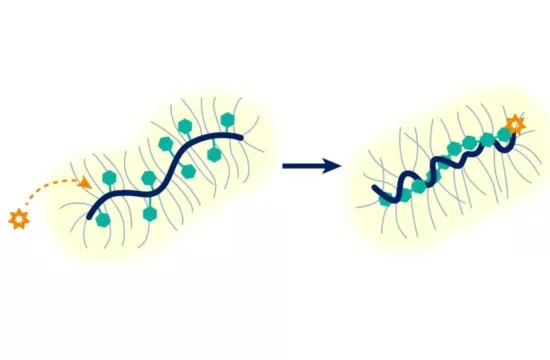

“It’s an entirely different system even at the genetic and molecular level than the one that encodes normal memories,” said Vladimir Jovasevic, the lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at Northwestern at the time of the work.

The entire system is governed by a micro RNA known as miR-33 – and could be the brain’s protective mechanism, they added.

“State-dependent learning” is a theory that memory formed in a particular mood can best be recalled when the brain is back in the same state – whether that is aroused, drugged, happy or sad, according to experts. A British study of the phenomenon published in 1997 found that recall was superior based solely on emotional mood of subject.

The debate over repressed memories has been intense, and occasionally bitter, because of its importance as evidence of childhood abuse and other phenomena. A 2001 study published in Applied cognitive Psychology found that traumatic memories were special and differentiated from normal memories – but didn’t point to any unique pathway of creating those memories.