Until the arrival of the international Cassini–Huygens mission at Saturn in 2004, much about the gas giant, its intricate ring system and enigmatic moons was a mystery.

On 14 January 2005, the mystery as to what lay beneath the thick atmosphere of Saturn’s largest moon Titan was to be revealed as ESA’s Huygens probe made the first successful landing on a world in the outer Solar System.

During the two-and-a-half hour descent under parachute, features that looked remarkably like shore lines and river systems on Earth appeared from the haze. But rather than water, with surface temperatures of around –180ºC, the fluid involved here is methane, a simple organic compound.

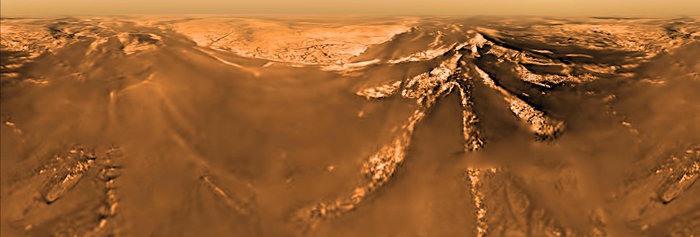

One set of images taken by Huygens is pictured here showing the view from 2 km altitude. It is in Mercator projection, so the N–S/E–W directions cross at right angles but surface areas appear distorted.

Huygens touched down on a frozen surface littered with rounded pebbles, and continued to transmit to its mothership for 72 minutes before Cassini dropped below the horizon. The stream of data returned from the surface provided a unique treasure trove of in situ measurements that scientists are still mining today.

In its 13-year odyssey of the Saturn system Cassini made 127 close flybys of Titan, including radar-mapping its surface – even before Huygens’ descent – and finding numerous hydrocarbon lakes and seas, evidence for a global ocean of water beneath its thick crust, and an atmosphere teeming with prebiotic chemicals. Titan’s atmosphere is thought to be similar to early Earth’s before life developed, and thus can be seen as a planet-scale laboratory to understand the chemical reactions that may have led to life on Earth.

Cassini also watched Titan’s seasons change over time, including the development of a swirling vortex and clouds of methane rain that precipitate onto the surface.

Titan has also acted as a gravitational slingshot for Cassini throughout its mission, setting it on course for exploration of the Saturn system. Tonight (19:04 GMT) Cassini will make its last, distant, flyby of Titan, dubbed the ‘goodbye kiss’ by mission planners, taking it 119 049 km from its surface.

The flyby seals Cassini’s fate, causing the spacecraft to slow down slightly in its orbit around Saturn and lowering its altitude over the planet. Thus it will plunge into the atmosphere, disposing of the spacecraft in the safest way possible to avoid an unplanned impact into a pristine icy satellite, such as ocean-bearing Enceladus.