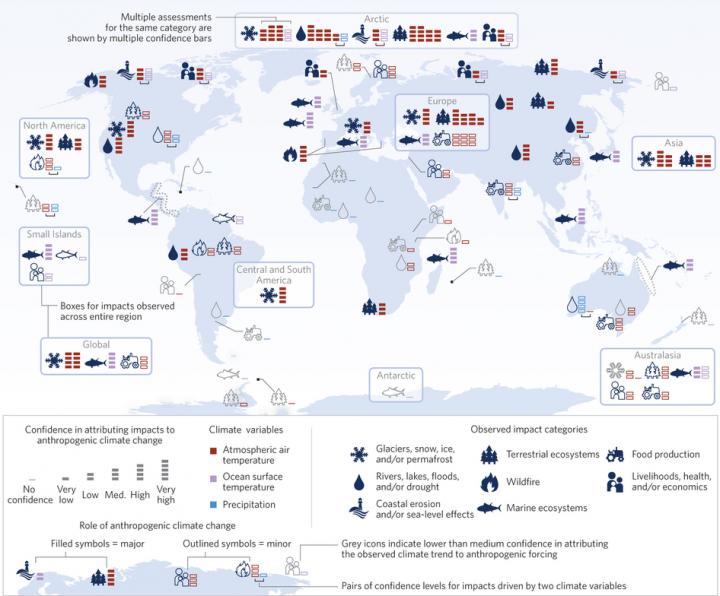

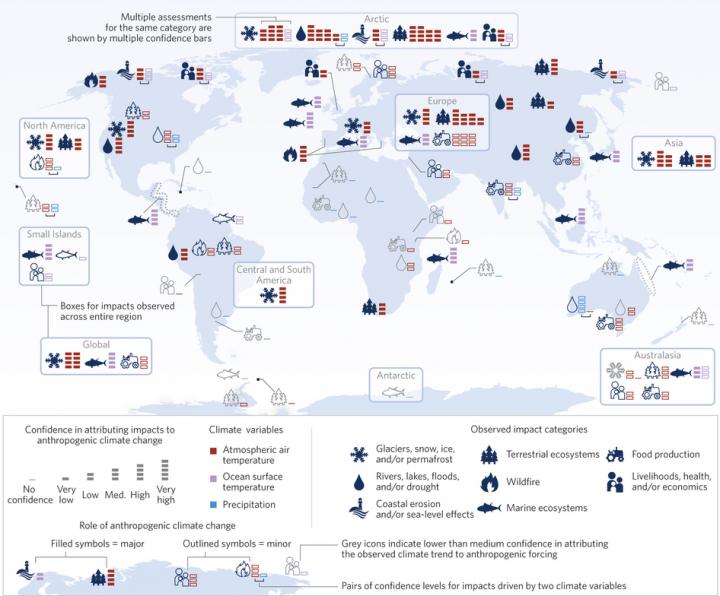

Melting snow ice and glaciers in Europe, changes to the terrestrial ecosystem in Asia, and wildfires in the state of Alaska. In the last century, the global temperature has increased by 1.4 F, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the aforementioned are just a few of the observable changes in regions around the world. But just how much are humans responsible for climate change?

Using over 100 climate impacts reported by the IPCC and computer modeling, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research found that almost two-thirds of the listed climate changes are attributable to human-generated emissions.

[pullquote]The data set was then combined and resulted in a numerical score, which was indicative of whether human-generated emissions were a factor in affecting the regional climate data over the decades.[/pullquote]

“Previous analyses linking observed impacts to climate change have been generic in nature, addressing whether there is an influence of human-related warming on impacts globally, without an inference to individual impacts,” said Gerrit Hansen, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “Our analysis is the first to bridge these gaps for a large range of impacts, by assessing the role of human-related emissions in each impact individually, including impacts related to trends in precipitation and sea ice.”

Hansen and Dáithí Stone, of the Berkeley Lab, published their research in Nature Climate Change.They focused their study on regional climate trends over a 40-year period, between 1971 and 2010.

Their developed computer algorithm first assessed the adequacy of the observational record used. Next, it determined whether the regional climate data was sufficient in detail and provided sufficient resolution. The researchers then examined model simulations, some of which factored in human emissions while other didn’t.

The data set was then combined and resulted in a numerical score, which was indicative of whether human-generated emissions were a factor in affecting the regional climate data over the decades.

“There are many ways we could combine the scores,” said Stone, “but we found that it didn’t matter which plausible method we used—the results all pointed to the same conclusions.”

“We find that almost two-thirds of the impacts related to atmospheric and ocean temperature can be confidently attributed to anthropogenic forcing,” the researchers wrote in their paper. “In contrast, evidence connecting changes in precipitation and their respective impacts to human influence is still weak.”

The new study could help scientists better predict the future impacts of a warming global climate.

“With these tests, we can be much more confident in our calculations of how a 4 C world will differ from a 1.5 C world,” said Wolfgang Cramer, the director of the Mediterranean Institute for Marine and Terrestrial Biodiversity. “It is crucial that we continue to develop and maintain observational efforts around the world in order to continue documenting how the world is responding to our greenhouse emissions, as well as to agreed reductions in those emissions.”