The recent study of a Duke University has found that alike with human in case of framing the most preferable option, chimpanzees and bonobos too go for more positive spin to things.

For example, people will go for a burger labelled “75 percent lean mean” rating it to be more tastier than a burger with a label “25 percent fat” even though both means same except the term used to describe it. Also people are more reliable in a medical procedure when they are told that it has 50 percent chances to succeed than when they are told it has 50 percent chance of failure.

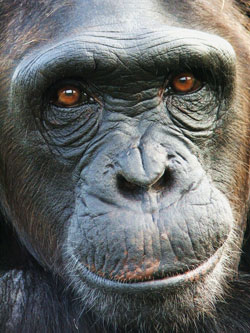

In experiments conducted at Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Sanctuary in the Republic of Congo and Lola ya Bonobo Sanctuary in the Democratic Republic of Congo, researchers presented 23 chimpanzees and 17 bonobos with a choice between two snacks — a handful of nuts and some fruit.

In one series of trials, the researchers framed the fruit option positively — by offering one piece of fruit, with a 50 percent chance of a surprise bonus piece.

In another series of trials, the researchers framed the fruit option negatively. This time they offered two pieces of fruit rather than one, but if the apes chose the fruit, half the time they were shortchanged and received only one piece instead.

Chimps and bonobos were more likely to choose the fruit over the nuts when they were offered a smaller amount of fruit but sometimes got more, versus when they were initially offered more but sometimes got less — despite receiving equal average payoffs in both scenarios.

The preference for the option framed as a prize rather than a penalty was especially strong in males, the researchers found.

Scheduled to appear in the journal Biology Letters, the study is part of a larger body of research on how psychological factors shape behavior and decision-making.

“People tend to prefer something more when you accentuate its positive attributes than when you highlight its negative attributes, even when the options are equal,” said Christopher Krupenye, a doctoral student in evolutionary anthropology at Duke who co-authored the study with Duke researcher Brian Hare and Alexandra Rosati of Yale.

“Historically, researchers thought these kinds of biases must be a product of human culture, or the way we’re socialized, or our experience with financial markets. But the fact that chimps and bonobos, our closest living primate relatives, exhibit the same biases suggests they’re deeply rooted in our biology,” Krupenye said.

“That means it’s very difficult to overcome these biases, but it is possible to create environments that might help us make better choices.”

Source: Duke University